Chapter 8

Price support, stabilization and the Common Wine Policy

Stabilization

As you will recall, Milhau’s (1935) advocacy for price stabilization rested on the argument that, demand for wine being price-inelastic, the extent of yearly fluctuations in harvest caused an excessively risky income to flow to the producers. It was thus proposed that the government operate a buffer stock, but leave the wines in the producers’ tanks. This option clearly put the wholesalers on the consumers’ side. The case was illustrated in Chapter Six, when it was assumed that all the profits the intervention agency would make in arbitraging the wines would be redistributed to the producers. The assessment of the resulting potential gains came to the somewhat surprising result that, risk benefit aside, producers would stand to lose from having a price stabilization programme implemented for them, though society as a whole would clearly benefit from it. It was found that the gains from arbitrage would only be part of a larger transfer of revenue, which would go from producers to consumers. Thus, to argue that wholesalers should not get any share in the arbitrage benefits appears legitimate. To try to prevent wholesalers from storing wines for speculative purposes lacks realism however. This reduces even further the potential gains from arbitrage and, with it, the attractiveness of the policy from the producers’ vantage point. It is perhaps worth recalling at this stage that the measure had been put forward as part of a struggle to establish a fairer balance of power between producers and wholesalers. Producers had little storage capacity in the 1930s and the co-operative movement was still embryonic. Since then French and common policies have brought about a significant improvement in the producers’ situation and one would find it difficult to argue today that producers need to be shielded against speculative action by wholesalers. More important, to suggest that the Council should opt for a buffer stock policy in order to stabilize income to the production sector, would ignore the fact that risk in income and risk in price can be dissociated from each other by hedging with futures.

Hedging is a technique which is used by businessmen who want to reduce risk in the price of the commodity they handle. It is widely applied in primary and agricultural markets, which are known to suffer a great deal from price instability. Hedging is also common practice in finance, where people like to protect themselves against future movements in currencies and interest rates. Prudent firms seek to work with stable prices. To them, hedging is an effective tool for keeping profits and costs under control. Banks which provide the necessary credit to hedge, have long accepted that fact [10]. To hedge in a particular commodity, one needs it to be traded on a futures’ market. Futures are a type of contract for forward delivery. First introduced for wheat on the Chicago Exchange in the 1860s, futures now exist for over forty items worldwide, ranging from beef to wood to orange juice, but not all markets are active enough to capture the interest of private investors [11]. Europe has been fairly late at introducing this novel form of contract. Amsterdam has had a futures market for potatoes for just over 25 years and London set up its own in 1980. London offers futures markets in wheat, barley, soybean, wool and pig meat, all of which have been set up fairly recently. Another successful addition is the London International Financial Futures Exchange.

There are now various futures markets scattered throughout Europe, but none for wine. Forward contracting has existed for a long time, for top Bordeaux wines (so-called vins primeurs). Similar contracts have been introduced recently in California for quality wines, under the inappropriate name of ’futures’ (more on the distinction shortly). Wine was once included in a list of potentially tradeable commodities (along with tomato paste, almonds and tuna fish) when plans were laid down for the creation of a futures market on the west coast of the United States, but the project failed to materialize [12]. The introduction of futures as a means of stabilizing gross income is worth serious consideration in the context of the CWP, for this would bear three major advantages over the recourse to a buffer stock programme. First, the policy would no longer discriminate buyer from seller, but speculator from hedger, thereby taking into account individual preferences towards risk. Second, futures would increase the efficiency of the market by making prices convey better information on prevailing market conditions and by refining storage decisions. Third, the introduction of futures trading would lead to an improvement in the quality of the wines produced. Requirements are twofold: wines must be sufficiently homogeneous to secure the viability of the markets over the longer term and futures trading must extend through the following harvest in order to produce stabilization. The first difficulty can be overcome through increased standardization of wines and greater use of blending, the second by initiating contracts which would span over a period of 15 months. The remainder of this chapter deals with these issues in greater detail. The discussion begins by drawing on simple arguments which have been put forward to convince managers and investors of the benefits of using futures in their daily activities [13]. To avoid undue complexity, one proposes to leave all technicalities aside, to concentrate on the sole economic aspect of the question.

Imagine a risk-averse wholesaler, who buys table wine in bulk, blends, packages and sells under his own brand name to a series of food stores and wine shops in the Capital. His premises are located just out of town, far from the producing regions. This is not just to reduce transportation costs, but also to keep in close touch with his customers. His policy has been to offer them good wines at reasonable and stable prices – the key to the success of his operation. The wholesaler carries out particularly sound financial plans (cash flows) and issues price lists well in advance to his customers, so he may plan his purchases and carry out his deliveries in the most cost-effective way (he lays much emphasis on minimizing storage space and transportation costs). Here, one of his prime concerns is to avoid the risk that wine prices may rise between the time he issues a price list to his clients and the time he actually pays for the wines he orders from the producers, usually on the day of delivery. Suppose, in March, our wholesaler runs into a reliable producer who agrees to sell him wines at today’s price, but for delivery in November. The producer does this because he fears that prices might fall between now and then. The wholesaler, on his part, is very much concerned by his need to ensure adequate supplies to his customers for the Christmas peak period. Producer and wholesaler strike a deal. The price they agree upon is the current cash price plus a premium to cover interest rates and the cost to the producer of storing the wines until delivery. What the parties would contract here is known as a forward. Forwards are interesting because they allow risk-averse buyer and seller to eliminate the price risk between now and the time of delivery, when cash payment would occur otherwise. The drawback with forwards is that they are binding commitments and, hence, cannot be interchanged. The parties are almost irremediably tied up to their commitment to deliver or take delivery of the commodity. As hinted earlier, forward contracting is commonplace in Bordeaux and is now used in California, but the practice is restricted to top quality wines, which are high in demand. These forward contracts are initiated shortly after harvest has taken place, but well before the wines are put to market. The idea is merely to get buyers to finance stockholding for the producers (recall, aging can extend over several years). Not much can be drawn from these very restricted markets, except the interest of the wholesalers in planning well ahead when quality is assured.

Futures are similar to forwards, but interchangeable and, thus, tradeable. The Chicago Board of Trade (1982, p. 8) defines them as ‘legally binding commitments to deliver or take delivery of a commodity at a price agreed upon in the trading pit of a Commodity Exchange at the time the contract is executed. The seller has the option to deliver the commodity sometime during a specified future delivery month.’ Futures are standardized with respect to quality (there are various specific grades), size of order (a standard quantity) and date of maturity (the month of delivery). It is standardization that gives rise to interchangeability which, in turn, allows hedging to take place. Interchangeability also brings a third party into play: financial investors. Investors are of greatest interest because they are willing to bear the risk of a price change, which risk-averse producers and wholesalers are so eager to avoid. Investors come up with outside capital, their own money, to finance the risk in price. They are more commonly referred to as speculators, because they have no interest whatsoever in handling the commodity. What attracts them is the prospect of making large profits fairly quickly, in buying and selling futures skillfully (they hope to succeed in anticipating correctly the price changes). Interchangeability of the contracts enables them, later, to free themselves of the commitment to make or take delivery of the commodity, which they undertake when they purchase a futures contract. To free oneself, one simply offsets one’s position with an equal and opposite order, sometime before delivery is due. Take risk‐inclined Mrs Thatcher, who, in March, would buy 10 hl of November futures in table wine, for just $ 10,000 (November is the delivery date) [14]. The price for November futures climbs by 30 % in June the same year, shortly after publication of grim forecasts concerning harvest. At that point, she decides to offset her position and instructs her broker to sell immediately 10 hl of November futures. This leaves her with a gross profit of $ 3,000 [15]. Futures markets being sophisticated financial markets, she did not even have to pay a full $ 10,000 when she bought the November futures, back in March. She wrote a check for $ 2,000 only, agreed she would invest ’on margin’. In doing this, she was to benefit from an attractive leverage of ten to two on her investment which, in this case, would bring her a return of 150 % in just three months. Conversely for losses: buying on margin means that one may be called on to put down additional money in order to cover the margin, should futures prices fall.

Futures are higher-risk financial markets and, as such, they attract investors who wish to increase their risk (let alone because some wish to spread it). The attractiveness of futures comes from the fact that the same market can be used by people who wish to reduce the risk in their daily handling of the commodity, whether they be producers or wholesalers. A risk‐averse producer, for instance, would use a selling (short) hedge, as he expects to hold a certain amount of the commodity in the future, but wants to sell it now, for delivery later. A typically risk-averse wholesaler would place a buying (long) hedge. He knows that he will need the commodity sometime in the future, but prefers to buy it now, also for delivery later. What hedgers seek is some form of protection against adverse movements in price, against a fall in the producers’ case, a rise in the wholesalers’ [16]. Hereafter, one assumes that no information is available at the time a hedge is placed, about the market conditions that will prevail when the contract comes to maturity, i.e. when the commodity is due to be delivered. The reason for this particular restriction will soon become apparent. It is noteworthy that, in practice, the vast majority of the contracts are settled by offset, so that only a fraction (one to three percent) of the volume traded result in the actual delivery of the commodity [17]. A clearing house is usually attached to the exchange, which takes care of all the contracts in need of physical settlement. The house matches buyers and sellers, so that the deliveries can take place.

One calls the basis the difference between cash price (the current market price for the commodity) and futures price (the price for a specific futures contract). The basis turns out to be a good approximation for the carrying charges between the time of purchase of a futures contract and the date it bears for delivery. Carrying charges are the sum of storage, financial and insurance costs, minus convenience yield (the benefit one can derive from having the commodity ready for use). Action by arbitrageurs will tend to stabilize the basis. Here, the term ’arbitrageur’ refers to someone who handles the commodity, but chooses to speculate with it. These are risk‐inclined producers and wholesalers, whose attitude is basically the same as Mrs Thatcher’s, given they all choose to increase their risk. Arbitrageurs will follow an optimal storage rule, which will tell them to buy on the cash market and sell for future delivery when the futures price is significantly higher than the cash price. They will do this until it does not pay anymore, i.e. until the basis is brought back to a level where it only covers the carrying charges. Conversely for a situation where the cash price would exceed the futures by such an amount that it would now pay for arbitrageurs to sell the commodity on the cash market (from existing stocks) and buy it on the futures market.

The principle upon which hedging works is to substitute the risk in the cash price with the risk in the basis, which is reckoned to be smaller. The Chicago Board of Trade (1982, p. 64) claims that the basis is more predictable and more stable than either the cash or the futures price taken individually. Cash and futures prices move much in parallel with each other (both react to the same economic news), thus their difference remains fairly stable. This argument is to be set against the popular belief that trading by shrewd speculators (Mrs Thatcher and the like) would unsettle cash and futures prices to the extent that producers’ incomes would be destabilized. There has been a fair amount of controversy around the issue, but the detractors of the stabilizing properties of futures trading have yet to come up with more convincing arguments or conclusive evidence for their claim [18]. The debate has been formulated in fairly general terms so far and there is a simple way of ensuring stabilization in the specific case of table wine. More on this later and on to the hedger’s individual basis. The actual price one would receive when selling the commodity to the exchange, is the cash price quoted there minus transportation costs from one’s operation to the nearest delivery point set up by the clearing house (it is assumed there is only one such location, situated at the exchange itself, to simplify). Similarly for one who would buy the commodity from the exchange. The price one would have to pay for the commodity is the official cash price plus the cost of delivery from the exchange to one’s operation. Transportation costs from and to the exchange being assimilable to the carrying charges for any individual hedger, these are now introduced in the hedger’s basis. The typical pattern for one’s basis is that it will narrow down to the sole transportation costs as the time of delivery approaches. Should one ignore carrying charges and hold transportation costs fixed, the basis would remain unchanged. This artifice is commonly used when dealing with numerical examples, again for the sake of simplicity. The literature calls this a perfect hedge.

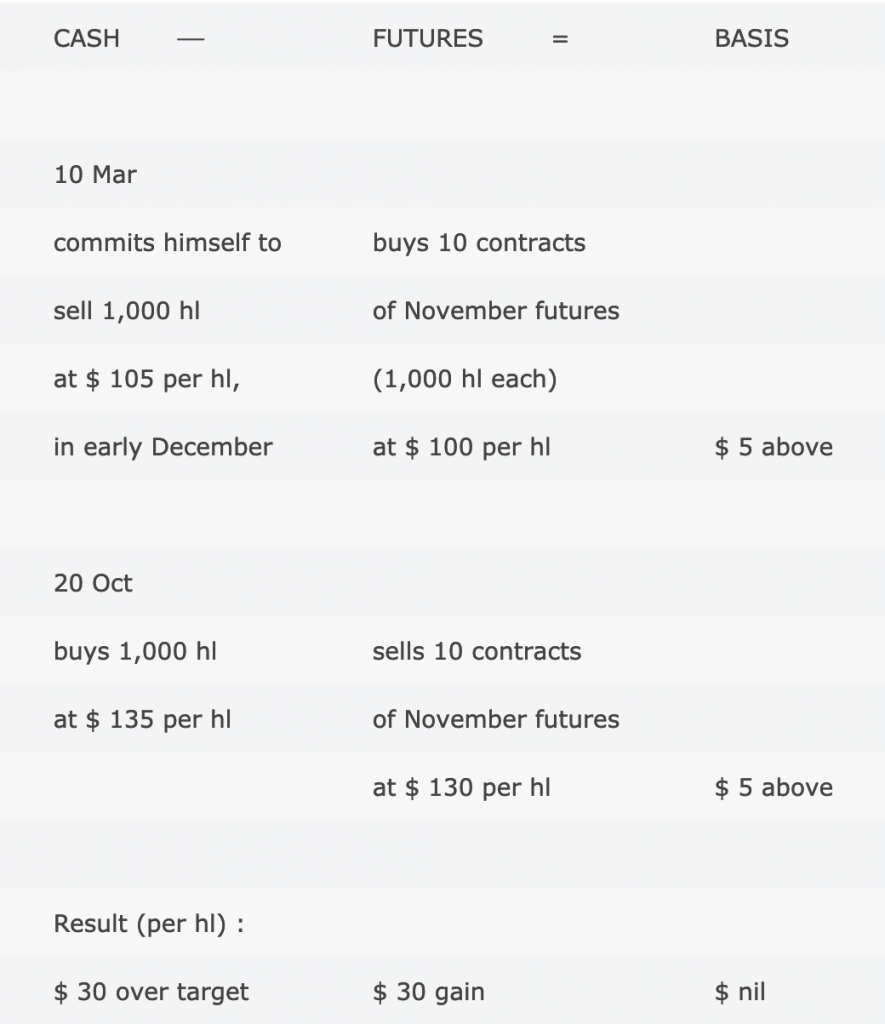

Take the wholesaler, again in March, and suppose he faces a futures market in table wine, also transportation costs of $ 5 per hl, from the exchange to his operation. On the 10th of that month, cash price and November futures are both quoted at $ 100 per hl [19]. The wholesaler strikes a deal with a small chain of supermarkets and commits himself to sell them 1,000 hl of table wine in early December, for a total of $ 105,000. Herewith his target price becomes $ 105 per hl. He hedges his cash position on the same day and buys 1,000 hl (10 contracts) of November futures, which he pays $ 100,000 in all. Meanwhile, harvest turns out to be relatively small and, on 20 October, local cash price and futures price are quoted at $ 135 and $ 130 respectively. The wholesaler buys the wines he needs for the supermarkets from one of his regular suppliers and asks for the wines to be delivered to him immediately [20]. He pays them a total of $ 135,000. This would normally put him at a loss ($ 30,000 above target), but on the same day he decides to lift his hedge and sells 10 contracts of November futures for a total of $ 130,000, which earns him a profit of $ 30,000. Gains and losses on futures and cash markets cancel each other out and his gross cost for the purchase of the 1,000 hl becomes $ 105,000, just as planned. Table 8.3 summarizes the wholesaler’s position and moves on cash and futures markets. Still it should be borne in mind that a perfect hedge would rarely happen in practice, so that the basis is likely to undergo slight changes, but a good knowledge of the yearly pattern for a particular basis would help one decide when to place and lift the hedge. One could also decide to ’roll’ the hedge, i.e. to switch to a contract of an earlier or later date of delivery, depending on the evolution of the market [21].

Table 8 .3 Wholesaler’s hedge

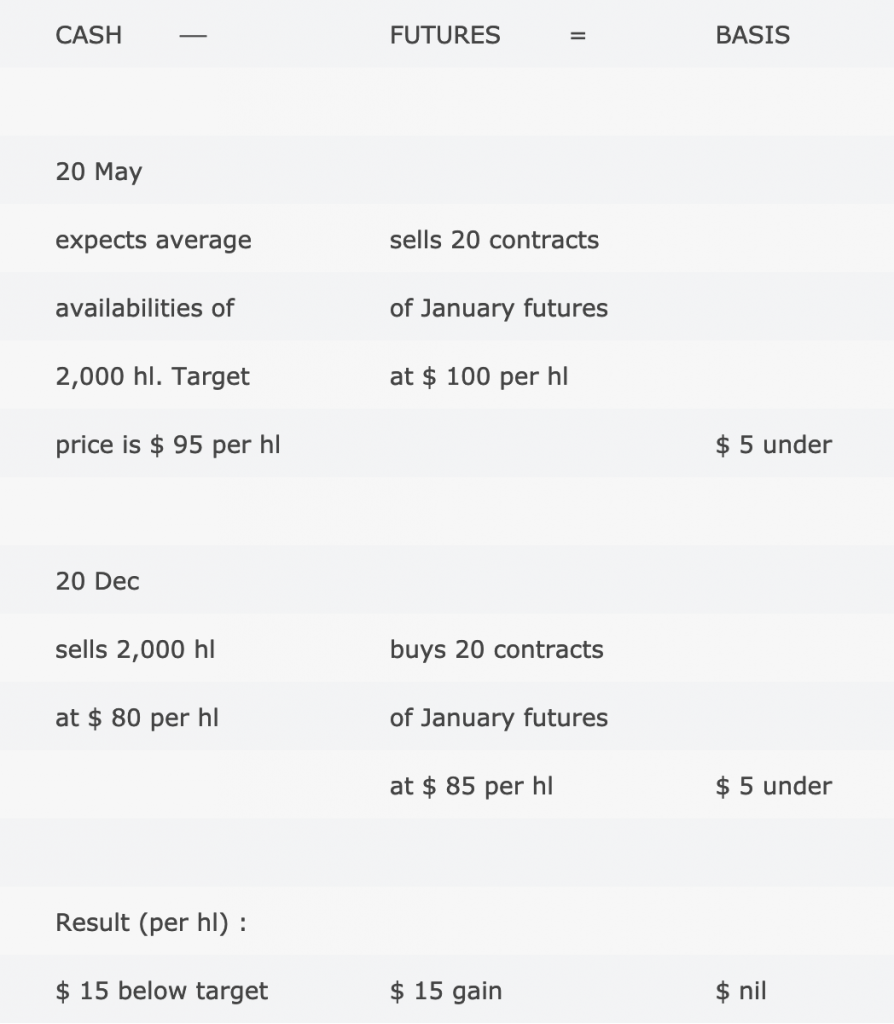

Consider again a perfect hedge – the selling hedge a producer would place in the fear that prices might drop below target by the time it comes to sell the wines. Take a producer who reviews his planning in May and suppose that, from all the wines he has presently in stock, he foresees to hold 500 hl still unsold at the end of the year. In addition to these, he anticipates to produce about 1,500 hl of new wines, from the upcoming harvest, in October. The new wines will be ready to sell by January, so he expects to have a total of about 2,000 hl to put on sale by then. The target price he has in mind is $ 95 per hl, for a turnover of $ 190,000. The cost he would incur for transporting the wines from the winery to the exchange are $ 5 per hl, as in the wholesaler’s case. On 20 May, January futures are quoted at $ 100 per hl. This suits him well and he decides to place a hedge by selling 20 contracts for a total of $ 200,000. A large harvest takes place in the meantime and, by 20 December, cash and futures prices have dropped to $ 80 and $ 85 respectively. Assuming the producer finds a local buyer for 2,000 hl, the sale would earn him only $ 160,000, $ 30,000 below his targeted turnover figure of $ 190,000. Still, on the same day, he would lift his hedge and buy 20 contracts of January futures for just $ 170,000, which would allow him to close his position on the futures market with a profit of $ 30,000. Gains and losses would even each other out and the producer could stick to his original plan (see Table 8.4).

Table 8.4 Producer’s hedge

So far so good, but suppose that prices rise instead, as the result of a poor harvest (identical prices to those for the wholesaler are used, to simplify). Back in May, the producer would have hedged all the same and sold 20 contracts for $ 200,000. Come December, he would close his hedge and buy 20 contracts at $ 130 per hl, for $ 260,000 in total, which would leave him $ 60,000 in the red on the futures market. His wines would now be worth $ 125 per hl on the local cash market, well above his targeted price of $ 95. Selling these would earn him a profit, which he would use to write off the loss on the futures market. And now to the hitch : namely, a relatively poor harvest would leave the producer with less wine to sell than he would have hedged for, implying that he is likely to incur a small loss. The opposite situation had prevailed earlier still, when harvest was large. The producer was left with some extra wines then, which he could have sold on the cash market, earning him an additional profit. Would the extra profits cover the extra losses, on average? – how much would it cost hedging producers and wholesalers to operate a small buffer stock, for that and other conveniences? The figure is difficult to assess, for this will depend much on individual needs. Also, one would have to accept that, on average, speculators would earn a premium for bearing risk for the hedgers, though many investors might incur severe losses in the process. ’The essence of futures trading […] is the transfer of price risks from the hedgers to the speculators in return for a risk premium’ [22]. It is this premium which lures Mrs Thatcher into the market, to finance the risk for the more conservative agents. The literature calls this ’normal backwardation’ [23]. Finally, recall there are brokerage fees to take into account, so hedging is not exactly free. The cost of hedging is what thousands of commodity traders regard as an acceptable price to pay for running a less risky business and there is no reason to believe that the situation would be dramatically different in table wine. Trading in futures would enable skilled hedgers to reduce their risk in a substantial way, by stabilizing costs to wholesalers and returns to producers. If not perfect, then at least partial stabilization is possible, provided one initiates contracts which extend far enough into the future to carry through the next harvest and the market is in overall (long run) equilibrium. The proof is straightforward.

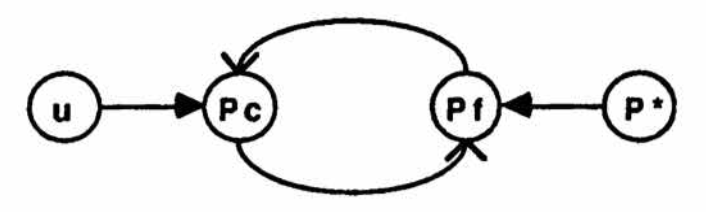

Suppose there were just one type of futures contracts, for delivery in 15 months. It was argued above, that cash price and (15 months) futures price would interact with each other, so one writes :

Pc = f1 (MP, Z, Pf)

Pf = f2 (MPe, Ze, Pc)

Pc and Pf stand for cash and 15 months futures price respectively; f1 and f2 are any type of functions and MP indicates the level of market pressure [24]. The vector Z entails all other price determinants, of which the level of financial pressure (the superscript e denotes expected values, as opposed to actual ones). Of MPe and Ze, it is the expected level of market pressure which is of greatest interest. Assuming there were no foreseeable change in Z and bearing in mind that fifteen months futures would carry through to ’uncertainty’ about market conditions (it was argued in Chapter Seven that the size of harvest varied sufficiently from year to year to ensure that, at all times, the best estimate for the level of market pressure prevailing 15 months later is its current average level), it follows that the best guess for the expected price for wine 15 months hence would be the systematic price P* (the underlying long run equilibrium price). Thus, abstracting from the Zs (in both actual and predicted values) and replacing MPe by P* in the second equation, this yields a solution, for the system, which looks as follows:

The left part of the diagram illustrates the impact of risk in supply/demand (u) on the cash price, a subject which was discussed extensively in Chapters Six and Seven. In the centre, interaction between cash and futures prices ensures that both prices move in line with each other. The right hand side shows the impact of ’uncertainty’ about future market conditions on price, the length of the contract being such that the systematic price works as an attractor to the futures price Pf, i.e. Pc > Pf > P* when MP is low; Pc < Pf < P* when MP is high [25]. In other words, letting market conditions vary and keeping all other things unchanged, the futures price would stay closer to the systematic price than would the cash price. Producers who would place their hedge at Pf could thus sell most of their harvest forward, at a near equilibrium price. A similar argument applies to the wholesalers’ hedge. One would thus get more chances to stabilize income to producers and costs to wholesalers with the futures price than with the cash price alone.

Note that a single futures price has been considered so far, for delivery 15 months later. Practice would call for trading in shorter contracts just the same, the terms for which would depend on what the actual delivery dates would be. Suppose there were four delivery dates a year: January (the usual time for producers to start releasing the new wines to market), April, July and October. This would generate a string of four futures prices, which strong interaction would bring to fluctuate in sympathy with each other, in between Pc and Pf. Accordingly, there would be no perfect stabilization, only a partial reduction in income variation, nor would there be any other guarantee but the skills of the hedger, for him to pick up a futures price which is nearest to P*. In practice, sellers (producers) would try to select the timing, for their hedge, in such a way as to get a price that is higher than the systematic price. Conversely for buyers (wholesalers), who would seek to hedge at below that level. Both actions are likely to balance each other, so that Pf would again tend to equilibrate at P*. If all it takes to partially stabilize gross income to producers and gross costs to wholesalers, is to introduce 15 months futures, then why not go ahead and set up futures markets for table wine? It does not seem unreasonable to think that conservative agents would plan 15 months ahead if, in return, they could seriously reduce their risk.

Trading in contracts which would extend as far as 15 months into the future, would stabilize incomes and costs with respect to yearly fluctuations in market conditions. Producers would be free to contract additional forms of insurance against specific hazards if they wished to do so (e.g. against hail, pests and, soon perhaps, radioactive fallout). Adequate credit facilities could then be used to dampen variations in interest rates, though hedging in itself would ease financial pressure. McKinnon (1967, p. 84ff) argues that futures trading would reduce capital rationing, which risky incomes are known to generate. McKinnon was first to suggest that producers run a small buffer stock jointly with hedging if they wished to stabilize their income (cash flow) [26]. His demonstration rested on the restrictive, though here familiar assumptions that random shifts in supply are the only source of price fluctuations (stability and linearity of demand for over the region of interest), production decisions are fixed (absence of supply response to futures prices), and futures trading spans the period over which the major price fluctuations occur (futures trading must carry through the major adjustment in price) [27]. An analogous case to that of producers could be made for the wholesalers. McKinnon’s arguments can thus be viewed as a further proof of the stabilizing properties of futures trading, as applied to the case of EC table wine, and of the relative insignificance of the cost for the hedger to monitor an individual buffer stock.

Note that futures trading would also bring about a significant improvement in market efficiency, not least because the most distant futures price would reflect much of what the agents think is the current level of P*. The need to preserve investors’ confidence would preclude all form of direct intervention on either cash or futures markets (there would be too much suspicion that the market be biased in favour of the producers otherwise), so that both prices would be free again to perform their informative role about the state of the market [28]. The analysis of price changes in Italy and France has shown that these reflected short term adjustments in the main (absence of cycle or memory). Wine prices have become not only more stable, but also more depressed and less efficient over time, so that they now convey poor information and, as such, can only send fuzzy signals to the decision makers. Wineries did not appear to follow an elaborate rule for storage either, with changes in inventories looking merely like a delayed shift in supply (stocks are kept fairly large in France, where they last until early April on average [29]). As noted earlier, futures trading would lead to a better coordination of the storage activity, which would be performed at the lowest expected cost [30]. Better storage and better information: futures could only improve the efficiency of the Community’s market in table wine.

Taking welfare gains, one would need to differentiate between hedgers and speculators, a role which was previously restricted to the intervention agency but would now be carried out jointly by arbitrageurs and financial speculators. Hedgers would benefit from a substantial reduction in the risk they would otherwise have to bear, whereas speculators would share the benefits from arbitraging the wines. The distinction between producers and consumers loses all relevance here and so does the issue on the transfer benefit. The risk benefit may prove impossible to assess because of the difficulty of accounting for each agent’s individual degree of risk-aversion (which may also change with time), but the major advantage of using futures, over a conventional buffer stock policy, is that this would leave everyone free to act in accordance with one’s own preference towards risk [31]. It would then fall on grape growers and wine producers who wish to reduce their risk, to agree on how to pass stability. This boils down to an accountancy issue for co-operative wineries, to the signing of private agreements between grape growers and local wineries in the other cases. Some of the contracts presently in use for quality wines stipulate that the price paid each year by the winery, for the grower’s entire harvest, will be indexed to the price of the wines sold concurrently by the winery. Businessmen rarely prove unimaginative when it comes to pounds and pence, so one can be reassured that wineries would find attractive ways to ’share’ the benefits from reducing risk with their grape suppliers (wineries have their own vineyards in many cases anyway [32]).

The greatest challenge in creating futures markets would reside in defining them correctly. The markets need to be large enough to remain active, but size will depend on the homogeneity of the wines. Homogeneity can be assured to a large extent through blending. The clearing house (winery) would blend the wines it receives in order to offer a fairly standardized product to those wholesalers interested in taking delivery of the wines (which could be used for further blending). Stringent criteria would have to be imposed for the wines to qualify for trading if futures markets are to attract enough wholesalers to keep them going over the years. Producers who would use futures to hedge but would then decide to deliver the wines, would be required to enclose a sample of the wines in their letter of intent to deliver, the usual document one sends to the exchange in those circumstances. The sample would be used to pass or reject the wines and, later, to verify the delivery corresponds to the sample. Should a producer’s wines be rejected, he would have to close his hedge (buy forward) at his own risk. Promoting quality becomes self-enforcing here. Futures wines could turn into a class of upper-quality table wines.

Futures are nothing fancy. Computerization, financial deregulation and technological change in winemaking (one’s ability to produce standardized wines) are turning futures into a serious option to the policy maker, that could help him bail the market out of its present difficulties. Liberalization should not affect the Community’s trade regime with third countries however. Protectionism may run against the spirit of GATT, but it is doubtful that one could afford to expose such long-term investments to the whims of world production and trade (one is talking of a fairly large trading area in any event). The chances are, that in adopting a policy which combines futures trading and restricted supply, the Council could then gear output to demand with relative case. It would also offer a major opportunity to stabilize income (cash flow) to those who want it, improve market efficiency and boost quality. Last, better consideration would be given to the interests of the consumers.

* * *

NOTES

[10] Brighton (1983, pp. 121-6), Chicago Board of Trade (1982, pp. 61, 70), World Financial Markets, December 1986. [11] Granger (1983, p. 19). [12] Granger (1983, p. 20). [13] The examples which follow are adapted from those given for wheat by the Chicago Board of Trade (1982). [14] One assumes there is only one type of wine and one grade of quality, to simplify. [15] There are brokerage fees to take into account. [16] Brighton (1983, p. 121). [17] Chicago Board of Trade (1982, p. 31). [18] That futures trading would destabilize prices in a way which would harm producers is a view that prevailed in US Congress in 1958, when trading in onion futures became prohibited, also in 1974, when amendments were brought to the Commodity Exchange Act. Peck (1975, 1976) is amongst those economists who have claimed that futures trading would fail to bring about more stable incomes, though she has accepted that, in facilitating storage decisions, futures would dampen price fluctuations. Newbery and Stiglitz (1981, Chapter 13) have drawn on Tomek and Gray (1970), to argue that futures trading would only offer a significant reduction in income risk to producers in the case of discontinuously stocked commodities. A l l “these authors consider supply response to futures trading in their analysis. However, Rutledge (1978) and Cox (1976) come up with strong evidence to undermine the above opinion. Both argue that speculation has either no effect on the variability of cash prices or that it actually helps stabilize them. In the vast majority of the cases in which Rutledge could identify the direction of causality between speculation (trading volume) and price variability, his evidence supported the view that price instability attracted speculators rather than was caused by them. See Rutledge (1978) for a brief review of the controversy, Cox (1976) for further reference to empirical work. [19] Recall, there is no differential to include a normal profit margin (carrying charges), to simplify. [20] Assumed are zero transportation costs, from the wholesalers’ to the stores. [21] See a trading manual for more details. [22] Houthakker (1957, p. 138). [23] Ibid.; Sheffrin (1983, p. 126). [24] See Chapter Seven for a definition of market pressure. [251 An attractor is an equilibrium position of the system. It is such that the trajectory of any point near that position goes to it, and no trajectory leaves it (Thom, 1969, p. 316). [26] McKinnon (1967) suggests quite rightly that one talks about cash flow rather than about income as soon as one introduces the possibility of building up or drawing down stocks (cash flow = pre-tax profits + the value of decumulated stocks and other write offs). [27] Average supply being fairly rigid and controllable in the case of EC table wine, it can be considered as fixed. Rigidity comes from the length of the production lag (two to three years), the extended average lifespan for the investment in vines (about 40 years) and the generally conservative attitude of the growers. Controllability proceeds from the fact that acreage is fixed and from the application of various structural programmes which, in principle, ensure that output be geared to demand. McKinnon (1967) assumes further that hedging is costless (absence of brokerage fees or normal backwardation), that output and prices have a normal bivariate distribution, and that the variance in income is a ’reasonable measure’ of risk. [28] Cox (1976) shows that futures trading increases the information incorporated in cash prices. Tomek and Robinson (1981, p. 190) argue that prices must be allowed to perform their economic function – that of rationing consumption and guiding production, if major problems are to be avoided. [29] Versus 10 February in Italy. Estimates were obtained by computing average market pressure at the beginning of the marketing year (for over the period 1951-80), from which one subtracted 12 months, representing the quantity necessary for covering demand up until next harvest. This left one with 7.2 months worth of consumption in the case of France (= early April) and 5.3 for Italy (= 10 February). Recall, there is no need for aging table wine. All that is required are a few months for fermentation to take place and for the wines to settle properly. [30] ’Futures markets were first developed for [continuously stored] commodities and have as their main function the coordination of storage and the reduction of inventory risks’ (Newbery and Stiglitz, 1981. p. 180). [31] ’An unbiased futures market […] provides unambiguously greater income risk insurance than perfect price stabilization. The reason is the standard revealed preference argument that an agent does better if he is free to choose the amount of price insurance as opposed to having a predetermined amount forced on him. [… This] does not, however, mean that producers necessarily prefer futures markets to price stabilization, because in general price stabilization will change the average price […], and so generates different transfer effects and supply responses (Newbery and Stiglitz, 1981, p. 177). [32] This type of contract is particularly advantageous to producers of quality wines. Vintage wines are typically released to market several years after crush has taken place (vintage year), meaning that wineries will ’cash in ‘ each subsequent increase in the cost of producing grapes, which might occur over those years. Conversely in the (less likely) case of falling prices for bottled wine or that of a reduction in the cost of producing grapes.* * *

REFERENCES

BRIGHTON, L.A. (1983) “Topics of Relevance to a Businessman”, in C. Granger (ed) “Trading in Commodities ‐ An Investors Chronicle Guide’. Woodhead-Faulkner, Cambridge.

CHICAGO BOARD OF TRADE (1982) “Commodity Trading Manual”. Chicago Board of Trade, Chicago.

COX, CC. (1976) “Futures Trading and Market Information”. Journal of Political Economy, 84:1215-36.

GRANGER, C. (1983) “The Purpose and Workings of Commodity Markets”, in C. Granger (ed) Trading in Commodities – An Investors Chronicle Guide’. Woodhead-Faulkner, Cambridge, 9-20.

HOUTHAKKER, HS. (1957) “Can Speculators Forecast Prices?”, in Peck (ed) ’Selected Writings on Futures Markets: Basic Research in Commodity Markets’. Chicago Board of Trade, Chicago.

McKINNON, R1. (1967) “Futures Markets, Buffer Stocks, and Income Stability for Primary Producers”. Journal of Political Economy, 75:844-61.

MILHAU, J. (1935) “Etude Econométrique du Prix du Vin en France”. Graille-Castelnau, Montpellier.

NEWBERY, D., and STIGLITZ, J. (1981) “The Theory of Commodity Price Stabilization – A Study in the Economics of Risk”. Clarendon, Oxford.

PECK, A. (1975) “Hedging and Income Stability: Concepts, Implications, and an Examp1e”, in A. Peck (ed) ‘Selected Writings on Futures Markets Basic Research in Commodity Markets’. Chicago Board of Trade, Chicago.

—– (1976) “Futures Markets, Supply Response, and Price Stability”. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 90:407-23.

RUTLEDGE, DJS. (1978) “Trading Volume and Price Variability: New Evidence on the Price Effects of Speculation”, in A. Goss (ed) ’Futures Markets: Their Establishment and Performance’. Croom Helm, London.

SHEFFRIN, S.M. (1983) “Rational Expectations”. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

THOM, R. (1969) “Topological Models in Biology”. Topology, 8:313-35.

TOMEK, W.G. and ROBINSON, K.L. (1981) “Agricultural Product Prices”. Cornell University Press, Ithaca.

TOMEK, WC. and GRAY, R.W. (1970)”Temporal Relationships Among Prices on Commodity Futures Markets: Their Allocative and Stabilizing Roles”, in A. Peck (ed) ’Selected Writings on Futures Markets: Basic Research in Commodity Markets’. Chicago Board of Trade, Chicago. © pierre spahni, 1988

© 1988 pierre spahni / www.span-e.com

* * *