ON GLOBAL WINE MARKET TRENDS

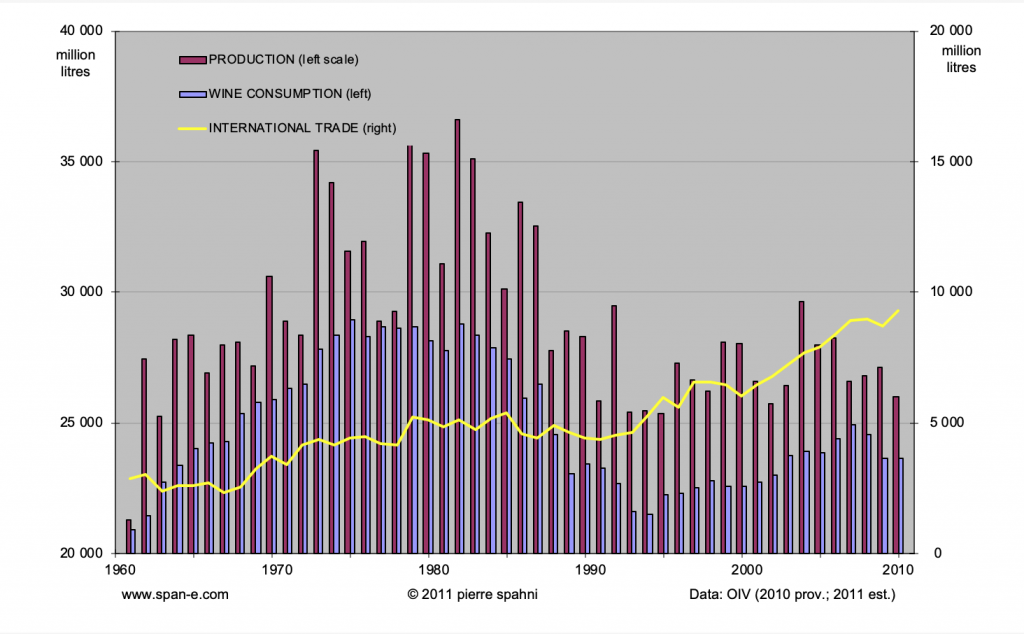

Few things have managed to contain the world’s growing thirst for foreign wines over the past 50 years. Volumes have trebled and now make up well over a third of the global market. This is roughly three times their share in the 1960s.

Largely responsible for this was the liberalisation of agricultural markets within the expanding borders of the European Community (beginning in 1970; truly free trade came about in 1992) and then amongst GATT/WTO member states (from 1995 onwards). WTO rules seek to reduce tariffs, subsidies and all sorts of trade impediments. There is even an Agreement (though as yet little consensus) on Trade-Related Intellectual Property Rights. A major fault line still runs between Old World and New World producers who have somehow rallied under the ‘World Wine Trade Group’ (WWTG) banner.

WWTG Members seek to promote wine trade through mutual agreement of existing oenological and labelling practices. Traceability is a major issue. ‘Bubble tags’ are unlikely to be featured on every wine bottle shipped across the Pacific tomorrow, but mutual recognition of each other’s wine certification procedures is clearly on its way. The WWTG is also now part of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum’s agenda. If China were to join the WWTG, this would definitively accelerate the current gentle drift of international wine trade flows away from the Old World towards the New and Emerging Worlds (see O-N-E World below).

The other major trend in trade since 1960 – the move away from shipping wine in bulk (en vrac) to shifting containers filled with bottles of branded wines offering better guarantees as to their quality and origin – is now ebbing back on economic and environmental concerns. Moving bulk is both cheaper and greener, and reducing carbon footprints has become a priority to producers wooing consumers at the other end of the world.

Meanwhile, globalisation has squeezed margins and put in the hands of retailers a powerful means of seducing customers away from their comfort zone, into trying out new wines: competitive prices. Provenance and brand name are two wine attributes that are used to build trust and reliable customer bases. But how far shoppers are willing to show their loyalty beyond merely displaying a store/fidelity card at the check-out counter is very much open to question.

Likewise for beer and spirit multinationals’ commitment to wine: the string of measures adopted for an eventual disposal of their wine units would indicate that many now feel they have reached the limits of workable synergies with wine, and stretched the patience of their shareholders with persistently lower levels of profitability. This in spite of wine’s rising popularity in non-traditional markets (wine’s relatively modest financial returns are one of the reasons why most businesses have remained in family hands).

Yet on the whole, wine has become a much more competitive business over the past 20-25 years – and largely for the best: the EU badly needed to be infused with a more competitive mindset. The relentless call for reforming the EU’s Common Wine Policy (or ‘Common Market Organisation for Wine’ as it is officially known) was a recurring theme in the material featured on this page in the past (see below). Most of the new EU legislation has since come into force and there is no major policy change in the offing, only strong opposition to the planned full liberalisation of planting rights after 2015.

I leave you with the commentary I made in the wake of the political decision to adopt reform in December 2007. ‘ Free rein‘ places that old note – and much else – in context.

April 8th, 2011

***

ON THE EUROPEAN UNION’S WINE REFORM

On December 19th, 2007 the European Union finally agreed on its wine reform package, after a few heated exchanges at the EU Council of (Agricultural) Ministers and 18 months of laborious consultations over the radical plans devised by the EU Commission [1].

As ever, the Council of Ministers opted for a diluted version of the original proposals tabled by the Commission. These were deemed excessively liberal as well as too pessimistic on the future prospects for global wine consumption and the capability of European producers to successfully engage their competitors on the world stage.

The Council of Ministers did agree to scrap distillation though. Its use as a market intervention tool will end in mid-2013, after 42 years of disservice (it was introduced as an exceptional measure when a common wine policy was laid down in 1970 and reinforced twice thereafter). Only distillation of the by-products of winemaking can remain, for environmental purposes. The EU is quite confident that ‘the changes will bring balance to the wine market’ [2]. Time will tell.

December 31st, 2007

[1] Communication from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament -Towards a sustainable European wine sector. COM(2006) 319 final. Commission of the European Communities, Brussels 22 June 2006.

[2] CAP reform: Wine reform will boost competitiveness of European wines. IP/07/1966.

***

© 2007, 2011 pierre spahni / www.span-e.com

You may quote or disseminate this article provided you make full reference to its author and website