PRICE STABILIZATION

Chapter 5

Introduction

Buffer stock policies were given so much attention during the past decade that they were eventually regarded as an almost prescriptive cure for price instability. In the 1970s, two notorious oil shocks and radical price changes for important primary and agricultural commodities began to strain trade relationships between developing countries and more advanced economies. UNCTAD reacted with its Integrated Programme for Commodities, a proposal to monitor large buffer stocks worldwide, in order to stabilize prices in cocoa, coffee, tea, sugar, tin and another five key commodities. It also issued recommendations to establish international agreements in various other markets, again based on the argument that programmes of this type would stabilize income to producers (developing countries) and expenditure by consumers (the industrialized world) [I]. The overall performance of UNCTAD’s programmes is thought to be mixed however and, recently, one of the schemes came to a spectacular halt. The International Tin Council (ITC), who monitored one of the best organized markets, ran out of money in October 1985 [2]. No one could be found in the financial community, who would agree on financing further operations by the ITC. This led to a temporary suspension of transactions on the London Metal Exchange, in the hope of avoiding a price collapse, but tin prices crashed as soon as trading resumed, leaving the ITC to default on debts of up to $ 1,300 million to creditor banks, metal brokers and the London Metal Exchange. Determined as they were to use the programme to support prices, the members of the ITC had accumulated stocks to the point of bankruptcy. OPEC, the oil cartel, ran into similar difficulties shortly afterwards [3].

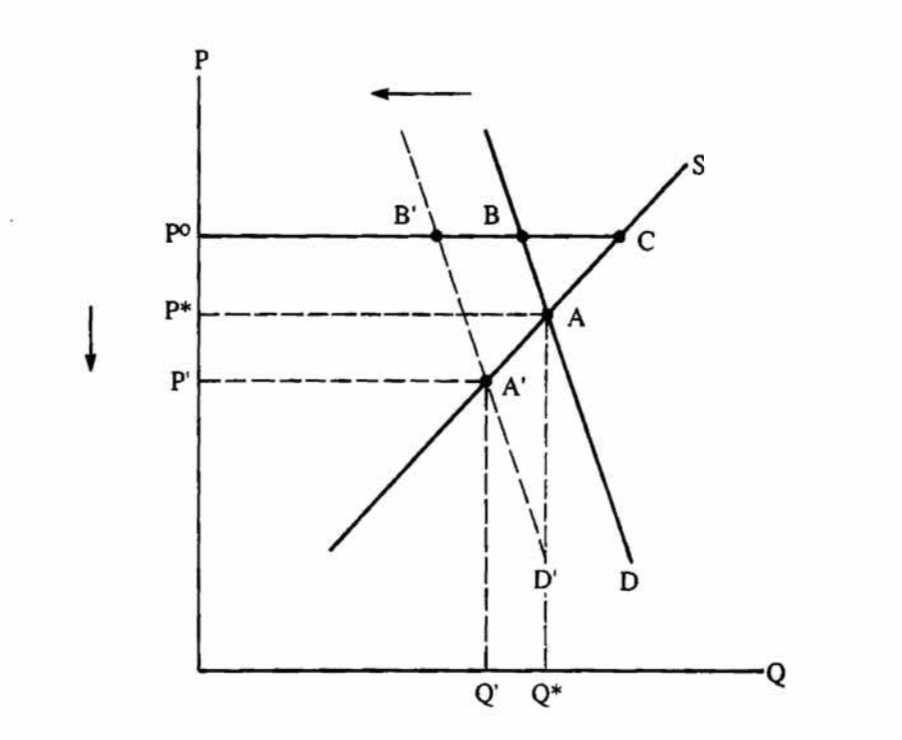

Figure 5.1 Support and substitution

Inflated prices have a relentless tendency to call for substitution by consumers (aluminium, glass and cardboard in the case of tin, other forms of energy in replacement for oil) and for a rise in output by producers. A surplus follows, together with lower prices. The process is illustrated in Figure 5.1, in a very simplified way (the model abstracts from all lags). Take a market which is in overall equilibrium (A) and consider demand to be fairly price inelastic. Supporting prices well above equilibrium, as in P°, reduces demand slightly and pushes up output slowly, leaving the difference BC to be removed from the market, into the buffer stock. The greater the inelasticity of demand, the fewer the possibilities for substitution in the short run and, hence, the stronger the incentive for consumers to search for substitutes over the longer term. Substitution will shift demand later to D’ and push equilibrium down to A’. Sustaining prices at the same level P° would call on the buffer stock manager to remove the additional quantity B’B, meaning that one ends up buying more off the market than one had planned initially, only to face a lower equilibrium price. The durability of the new situation depends on the shift in demand being reversible or not.

The running of an appropriate buffer stock in table wine would produce an overall welfare gain, which could be shared by all concerned, producers and consumers alike (more on this shortly). Biondolillo (1972) proposed to operate such a programme in order to stabilize wine consumption and prices in Argentina, based on a similar finding to that above. First to suggest the idea was Milhau (1935), who proposed that the French government stabilize producer prices and incomes with a buffer stock. The proposal came off shortly after the 1957‐58 price folly, when France decided to monitor a price band policy with the help of storage contracts. The Council of the EC began to grant similar storage aid to producers virtually from the outset of the Common Wine Policy (CWP), but the mechanism was deflected rapidly from any stabilizing role, to be used to support prices instead. The change of policy became definite upon the introduction of the garantie de bonne fin (GBF) arrangement, which pegged the price of wines under long term contracts to the activating price prevailing at the time the contracts were concluded. A mere 14 years later, the Council felt compelled to drop all short-term aid, because the measure had become ineffective in raising prices (sic). The drift from price stabilization to price support had been duly completed by then, in the same way as for tin.

Aside from this drift, controllability is probably the most difficult aspect of all in designing the appropriate buffer stock policy. Howitt (1979) contends that this issue has been given too little consideration by policy makers in the past, who have often ignored that even a stable economic system may prove uncontrollable in the end. This particular condition has yet to be established clearly for wine. To see how critical the issue is, just suppose that wine prices would move freely, with no explanation for the changes [4]. Surely, no one would think of applying a buffer stock policy in such poor conditions. Assessing the role played by random behaviour in the determination of wine prices is thus of utmost importance (the matter will be dealt with in detail in Chapter Seven). Last of all possible drawbacks in opting for a buffer stock policy is that it requires official interference. Is there no other, more efficient way of stabilizing wine producers’ incomes?

In their authoritative work on buffer stocks and commodity price stabilization, Newbery and Stiglitz (1981) came to the conclusion that competitive rules could yield more stable incomes to producers, provided these would use adequate futures markets (to hedge against risk in price and, possibly, against shocks in interest rates), and provided that additional forms of insurance were made available to them (e.g. against damage caused by pests in the case of wine). This proposition runs against the widespread opinion that bringing in shrewd speculators to finance risk for the hedgers would actually destabilize prices and, thereby, income to producers. Who is right? The (de)stabilizing role for futures in wine will be assessed later in this part. The next chapter begins by addressing the notion of stabilization, as this would result from implementing a proper buffer stock programme. Particular attention is given to partial stabilization, which only seeks to reduce, not fully eliminate price instability. Newbery and Stiglitz’ novel criteria for assessing the desirability of these programmes are then used to give proxies for the gains accruing at both ends of the market – to producers and consumers. The discussion focuses on the relationship between risk in supply (harvest) and change in price.

* * *

NOTES

[1] See Behrman and Tinakorn (1979, p. 113), Labys and Pollak (1984, p. 137). [2] The vast majority of the 22 members of the I T C are governments of producing countries. See Labys (1980, Chapters 2-5) for more details on identifying market structure and price formation for various commodities, including tin. [3] The Economist, 2 November 1985 and 26 April 1986; Financial Times, 24 April 1987. [4] Such is the claim made by the proponents of the Random Walk Theory in the case of the price of stocks. See Malkiel (1973), also Sheffrin (1983, Chapter 4) for further reference.* * *

REFERENCES

BEHRMAN, J., and TINAKORN, P. (1979) “Indexation of International Commodity Prices through International Buffer Stock Operations”. Journal of PoIicy Modeling, 1(l):l13-34.

BIONDOLILLO, A L. (1972) “Social Cost of Production Instability in the Grape-Wine Industry: Argentina”. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Minnesota.

HOWITT, R.E. (1979) Controllability – A Quantitative Test of Policy Institutions”. Working Paper, Department of Agricultural Economics, University of California, Davis.

LABYS, W.C. (1980) “Market Structure, Bargaining Power, and Resource Price Formation”. Lexington Books, Lexington.

LABYS, WC, and POLLAK, P.K. (1984) “Commodity Models for Forecasting and Policy Analysis”. Croom Helm, London.

MALKIEL, B.G. (1973) “A Random Walk Down Wall Street”. Norton, New York.

MILHAU, J. (1935) “Etude Econométrique du Prix du Vin en France”. Graille-Castelnau, Montpellier.

NEWBERY, D., and STIGLITZ, J. (1981) “The Theory of Commodity Price Stabilization – A Study in the Economics of Risk”. Clarendon, Oxford.

SHEFFRIN, S.M. (1983) “Rational Expectations”. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. © pierre spahni, 1988

© 1988 pierre spahni / www.span-e.com

* * *